One year at mozilla

My last post on this topic one month at Mozilla was posted as the title suggests when I just started.

My contribution at that point was a single pull request as I was struggling to understand what is happening and how things work.

Since then, I was able to do a bit more and here is a brief summary of my first year at Mozilla:

- submitted

119PRs intaskclusterproject. - created

40issues - helped shipping

3major versions to Firefox-CI and75minor + patch releases - fixed worker-manager bug that drove everyone crazy

- sent first patch to Firefox (1807667)

- attended or lead

27Taskcluster weekly Community meetings - improved developer experience

- was on approx

350+calls (according to Raycast wrapped) - met with

800+mozillians at the annual All-Hands - visited Berlin office

10+times - ordered

25+books of which managed to finish maybe5for now - learned truly a lot from the people who I work with or who worked there before me

Overall, I feel like this was a very productive year for me, despite all my fears and concerns at the beginning, when I was trying to figure things out.

That, of course, came with big support from the people I work with, big thanks and credits to:

- Pete Moore great patience and discussions about the golden age of 8-bit computing

- Matt Boris mastering dependabot and node/go upgrades

- Benson Wong guiding me on what to focus on

- Mathieu Leplatre reminded me how to use mercurial to contribute to Firefox

- Graham Beckley for sharing thoughtful articles, ideas and music

- Bryan Sieber for being goal-oriented

There are also many people outside of my team who influenced me in a positive way:

- Bastien Orivel from community who contributes quite a lot to the Taskcluster project

- Dustin Mitchell is a former Mozilla employee who keeps writing code even when he sleeps

- Jonas Finnemann Jensen was one of the authors of Taskcluster, created few cool things while at Mozilla

- whole RelEng team including Aki Sasaki, Andrew Halberstadt, Johan Lorenzo who support my team and provide valuable insights to the Taskcluster project.

- Michelle for trying to deploy Taskcluster the “hard way”

I had to spend some time to collect various bugs and issues that were important at that time. Here is that list. This list is huge, so we had to prioritize and decide what to work on. Below I list few achievements that I was able to accomplish.

Most notable achievements

- UI tests

- Firefox Remote Settings tests

- Dev deployment

- Worker Manager “slowness”

- Continuous Deployment

- Developer experience

- Metrics and visualisations

When I joined Taskcluster project it was mostly in a maintenance mode. Most of the original team left after unfortunate round of layoffs or its aftermath few years ago. The knowledge of the system was mostly lost or existed in some pieces in numerous places. Firefox CI which is the main deployment of Taskcluster that runs thousands of millions of tasks was not updated for many months and was haunted by some bugs that made whole service feel pretty buggy and slow.

Taskcluster consists of several micro-services that exist in the same monorepo and it had few issues that a new person joining this project might have:

- You could only run one or few micro-services locally while you do your development. You need to start each one manually, do some changes, add some tests, hope for the best and push.

- It was not possible to test your changes on some environment before you make a release. So often we would need to deploy release to be able to test it, and then ship few hotfixes right after.

- Dependabot sent many PRs to update UI packages, but no one knew if those will work because tests were not present

UI tests

To gain more confidence in frontend dependency upgrades I’ve switched testing from mocha to jest and improved coverage for most of the utils functions and few components.

I also added e2e tests with cypress. But the problem with E2E was that at this time I didn’t know how the system works or what to test, so it really covered just a simple case, and is still not running as part of CI jobs.

Having more tests helped to be slightly more confident in the merged dependency upgrades.

Dev deployment

Although Taskcluster had everything it needed documented and had the right set of tools, it was still quite tricky to deploy your own Taskcluster instance in the Kubernetes cluster.

Pre-conditions where to set up RabbitMQ instance and get the credentials, create Postgres DB instance in Cloud SQL, provision static IP and load balancer, manually issue certificate (which will later expire and you’d have to upload renewed one manually). Next you would have to manually configure DNS entries in Route53 to point to your dev deployment

Then, having all those necessary credentials you could yarn run dev:init that will ask few questions and generate big dev-config.yml containing all necessary values for the kubernetes templates that would later be deployed with yarn run dev:apply command. If you made a mistake, you’d have to repeat that process again, and some config steps were not obvious.

In order to simplify this I did few improvements:

- patched config tool and documentation on how to properly generate

dev-config.yml - added new utility tools:

dev:ensure:db,dev:ensure:rabbitto allow re-running some config steps separately, without the need to run whole config again - tested and documented how to install both rabbit and postgres into the cluster with

helmto be able to script all those steps without the need to use external services. In the end you could run one script to install rabbit, postgres and use those for the deployment

Still, the problem was to provision static IP, Load Balancer and create certificates manually. For this I’ve added ingress-nginx support and cert-manager to use LetsEncrypt to provision certificates automatically.

I was also able to configure a wildcard DNS to point to our single static IP on dev cluster so anyone could deploy his dev instance easily.

Major benefit was that we no more had to manually provision static IP, certificate and load balancer. By getting rid of GLB and using nginx-ingress we got more flexibility during deployments and re-deployments and saved time (no need to wait 5-10 minutes for GLB to pick up “healthy backends”). Provisioning of certificates was automated with adding few annotations and metadata to the config files.

Worker Manager “slowness”

No argue that Taskcluster is a very complex system that went through a lot of changes to get where it is today. One of the problems was to run thousands of tasks for any change you make in Firefox source code. Having multiple contributors results in tens and hundreds of thousands of tasks that needs to be executed somewhere.

Those tasks are executed by workers (docker-worker or generic-worker) that are running on any virtual or physical device. And the best way to do this was to create those machines on demand, based on the load.

Initial attempts were aws-provisioner) and ec2-provisioner. Which were later replaced by worker-manager.

Taskcluster has worker pools. Each worker pool belongs to provider (AWS, Azure, GCP, static) and specifies how new instances should be created (AMI, config, timeouts, etc). Each task is being claimed by a worker from specified worker pool (i.e. I want taskA to run on google/ubuntu-18.04 worker pool).

This way worker-manager can constantly check every worker pool to see if it has new tasks. Then using some simple estimations it can decide if new instances are needed, or existing capacity is enough. If new instances are needed, it will provision up to maxCapacity instances. Instances will be launched, workers would connect to Taskcluster and start executing those tasks, shutting themselves down once there are no new tasks.

Every once in a while, worker-manager would scan all workers that it started to see if they are still fine or need to be shut down.

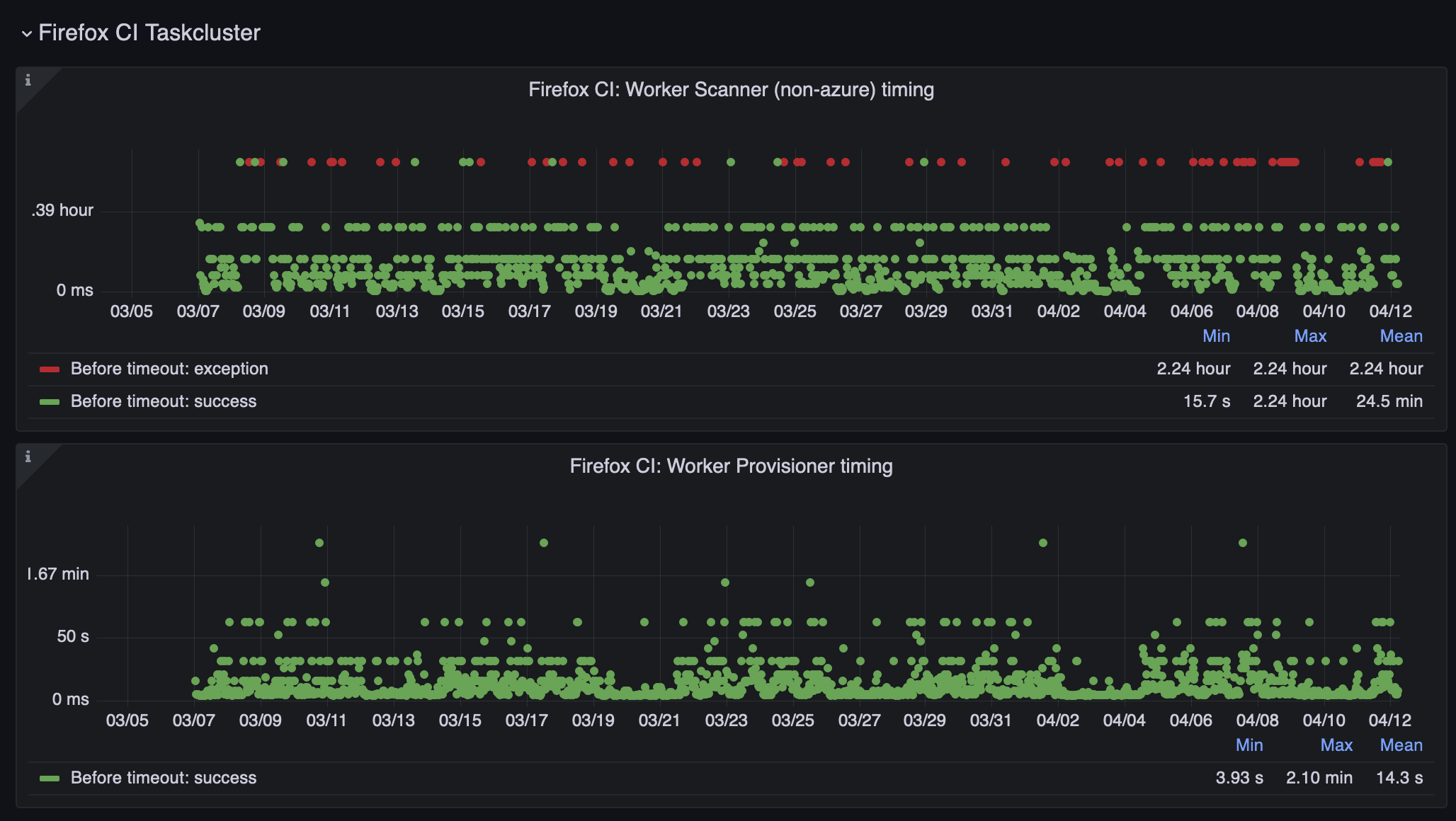

So essentially, worker-manager consists of provisioner loop (deciding how many instances to start) and worker-scanner loop (checking running instances status, stopping).

All works good … before the loop times out:

The red dots above says that the worker-scanner loop was timing out after about 2.5 hours. This means that not all of the workers could been checked, so system doesn’t know what state the worker is or to even know the exact amount of running capacity.

Digging into the the timeouts I’ve discovered that most of those delays come from one single provider (starts with A and ends with zure). And when you do thousands and thousands of calls daily you would inevitably run into all sorts of issues. But somehow it was only Azure.

How many API calls do you need to start new virtual machine? AWS - 1, GCP - 1, Azure - 3+! Yes, at least 3 calls to create a virtual machine (provision IP, provision NIC, provision Disks (optional), provision VM). Not to mention that Azure API is not very reliable.. calls take different amount of time to complete and sometimes hang indefinitely, which made us implement few timeouts to kill the calls that take too long (speaking of 10m+ here). And to add to this, provisioning of a single resource (pi/nic/disk/vm) is done in async manner, which means you need to: 1. request resource and get operation id 2. query if the operation with given id completed. So to provision IP/NIC/VM you need at least 6+ API calls. (Why Azure? WHY?)

Let’s get back to the worker-scanner who tries to do as much as possible as fast as possible. What happens is that it goes through every worker pool and checks all workers within that pool. When it gets to the Azure pools and some calls begin to take longer it cannot process other pools, times out and dies. Simply making this process parallel wouldn’t help, because you can easily hit rate limits and it would be even a bigger issue. Having single loop helps to control backoff timeouts and retries for cloud api calls easier.

So all of those timed out loops led to few workers being created on time, which led to stuck builds and hours and hours of waiting time to deliver anything. And if worker fails to start within a defined timeframe it will be killed. No wonder everyone was frustrated and overall impression was quite bad, but no one could figure out why everything is so slow.

There were few different solutions proposed in the past to this problem, like combining scanner and provisioner into a single loop. But this still would have an issue with timing out azure calls.

Without understanding how to fix this issue at the time, my first take was to separate bad providers into own isolated loop, that I could examine separately to figure out how to fix its slowness. So instead of merging both loops, I split it even more with creating separate azure scanner job.

Next small improvements where to realize that not all workers need Public IP, so we could skip IP provisioning and reduce total number of calls. Here we go, skipPublicIP was added.

Some calls take forever? Okay, let’s time cap it at 10min, which is insanely too much anyways.

And then optimize it a bit by requesting first resource from the provisioner loop immediately.

I’ve added few diagrams in the docs to display whole process. Check how insanely complex Azure checkWorker is.

Huh, alright.. so what good or bad did those changes do?

Turned out, that as soon as Azure pools were kicked out of the main loop, it automatically solved all the issues! Miracle. Worker scanner was not timing out anymore (or at least did it way less often), which means that AWS and GCP workers could start instantly now and serve incoming numbers of tasks. But also isolated Azure loop was seeing much less timeouts and was working more predictably.

After few weeks everyone who considered Taskcluster slow and buggy suddenly forgot about those issues. Tasks were being run on time, birds were signing, grass was green and sun was bright..

I was just lucky to be able to solve this issue in a relatively simple manner. Understanding and getting down to that solution took me few handful of weeks though.

Continuous Deployment

Ok, so as the main problem was solved, it was time to continue solving the problem of testing before the release is done. For this I experimented with GCP’s Cloud Build and it proved to be working great. Each new commit to main branch triggered build job in Cloud Build. New docker image would be built and stored in Cloud Registry.

Having up-to-date docker image for the main branch means that we can now use it to deploy to our dev environment. Using previously implemented changes it was trivial to create new environment https://dev.alpha.taskcluster-dev.net/ that will use ingress-nginx, cert-manager and deploy change there.

Later Matt Boris helped to create cloudbuild.yaml and put steps definitions in there. It could build new image, deploy it, remove older images as we no longer need them and run smoketests.

This was a huge leap forward because it allowed us to experiment and test features even before they would be released. And this happens within 10-15 minutes after branch gets merged to main.

Developer experience

Having own dev environment was already a big win, but still, it required merging your changes into main branch and waiting for the build to finish. So I started to build a docker-compose approach, that would allow to run all or required services locally and develop all or many services at once. This promised to be a huge win, because it would eliminate the need to build and deploy at all. You could just run everything locally.

However, it took more than one month to get there. Because every service has its own set of configuration options, own client ids, own credentials to access database, queue, apis, it required a lot of trial and error attempts to make it right. Huge credits go to Bastien for his contributions. He was able to provide valuable comments and patches to make things work together. Setting up local S3 storage with minio, showing few tricks how to use healthcheck conditions properly (service_healthy, service_completed_successfully), and how to set up minio and ingress properly.

Still, to run everything locally you’d need a lot of CPU and memory, as in addition to running main services, there were tens of background jobs. Sure, you don’t need all of them to run locally, but also I had no idea how to make services optional in docker-compose.yml so they wouldn’t be starting with docker compose up. Luckily it was a solved problem, as I discovered profiles, which I described in this post

So you could easily start just the API workers, and additionally include some background jobs with profiles as needed.

Next Matt Boris helped to add docker-compose.dev.yml and necessary yarn scripts so we could run some services in production mode and some in development.

By adding -devel image with nodemon it was possible to map local volumes and make dev containers to reload once the source code changed. (This is still an issue for UI though, as webpack inside docker works extremely slow, so running UI natively is a better approach for now)

This allowed to have full local development environment. Which included the UI, where you could login, create tasks, do everything as in production environments, call API endpoints and run tasks.

Running tasks locally proved to be a harder task, as it required containerizing generic-worker and bundling all its dependencies. In the end it was possible to make it running along with the services using same docker compose up.

Having those pieces of puzzle in place, made it possible for other teams to contribute easier.

Andrew Halberstadt was able to implement changes to the github service using ngrok to forward webhooks to the local services he was running with docker compose.

Metrics and visualisations

Alright, having those problems solved I was able to have some fun and add few missing features.

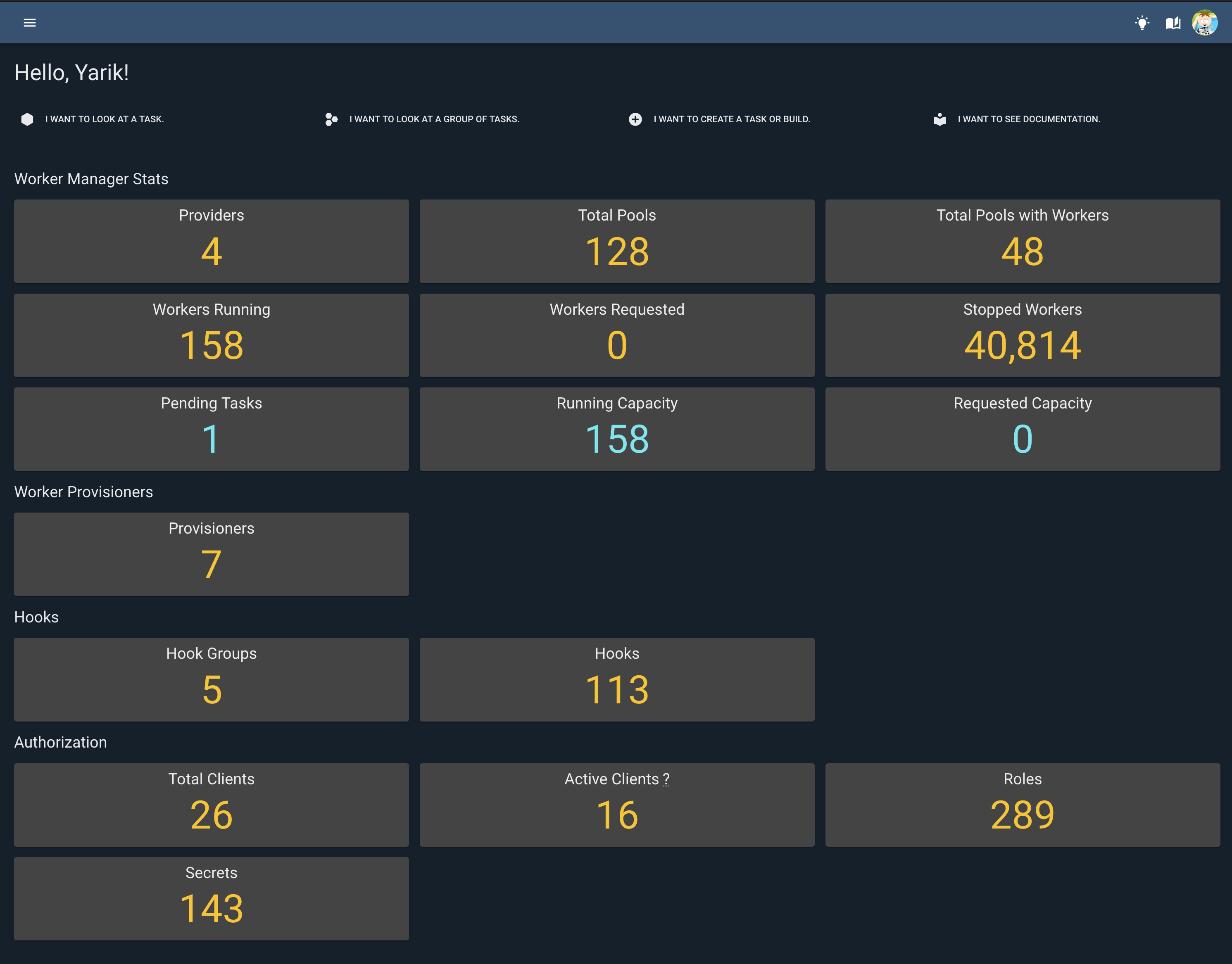

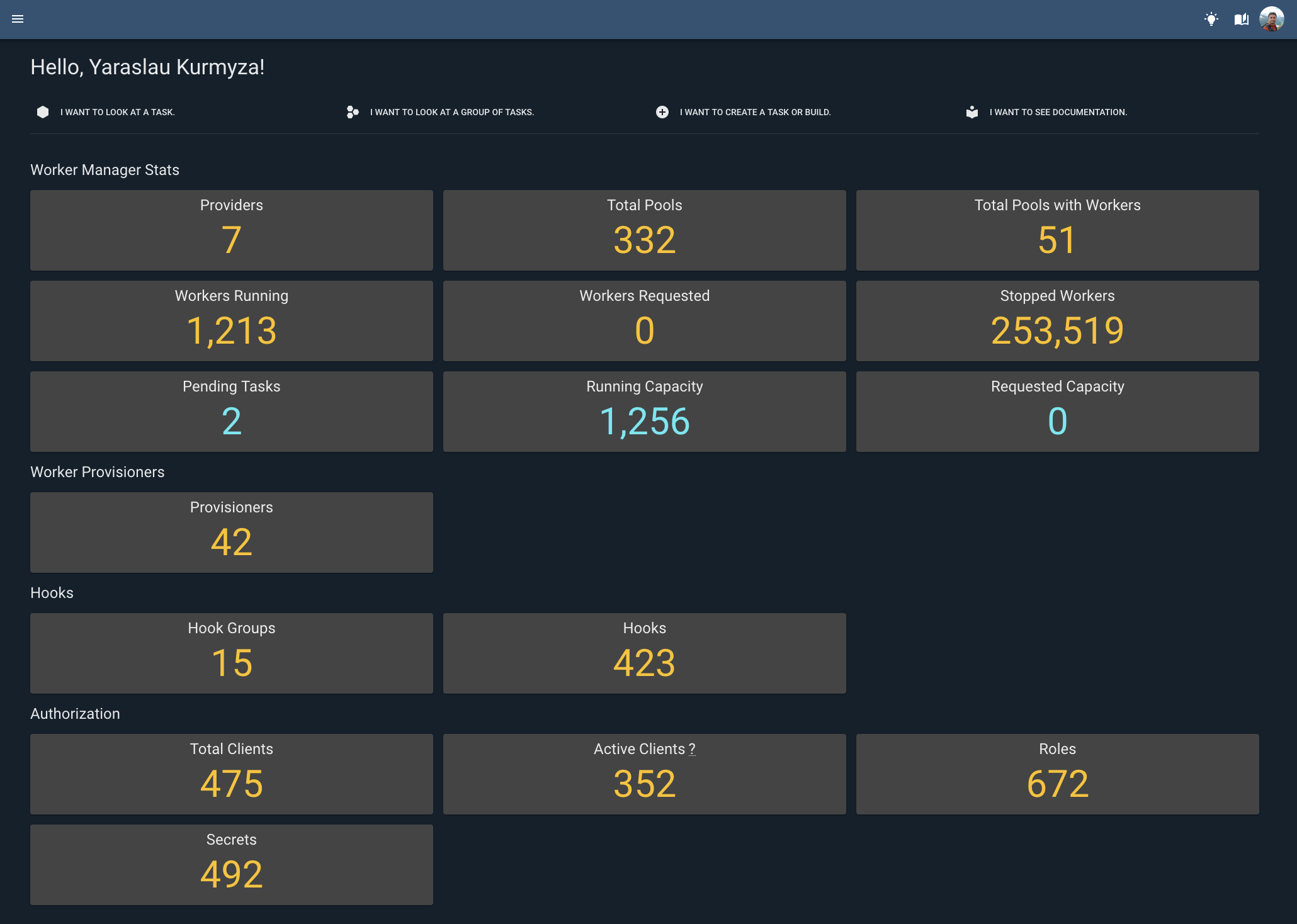

Dashboard

Taskcluster is big but you don’t know what’s happening inside. It is a distributed system and you don’t know that something is happening, or know what exactly is happening there.

I wanted to be able to see a few stats. So I added some stats to the dashboard:

Good, it is helpful to see how many pending tasks you have now, or how many workers were requested, or are running at the moment.

Timing

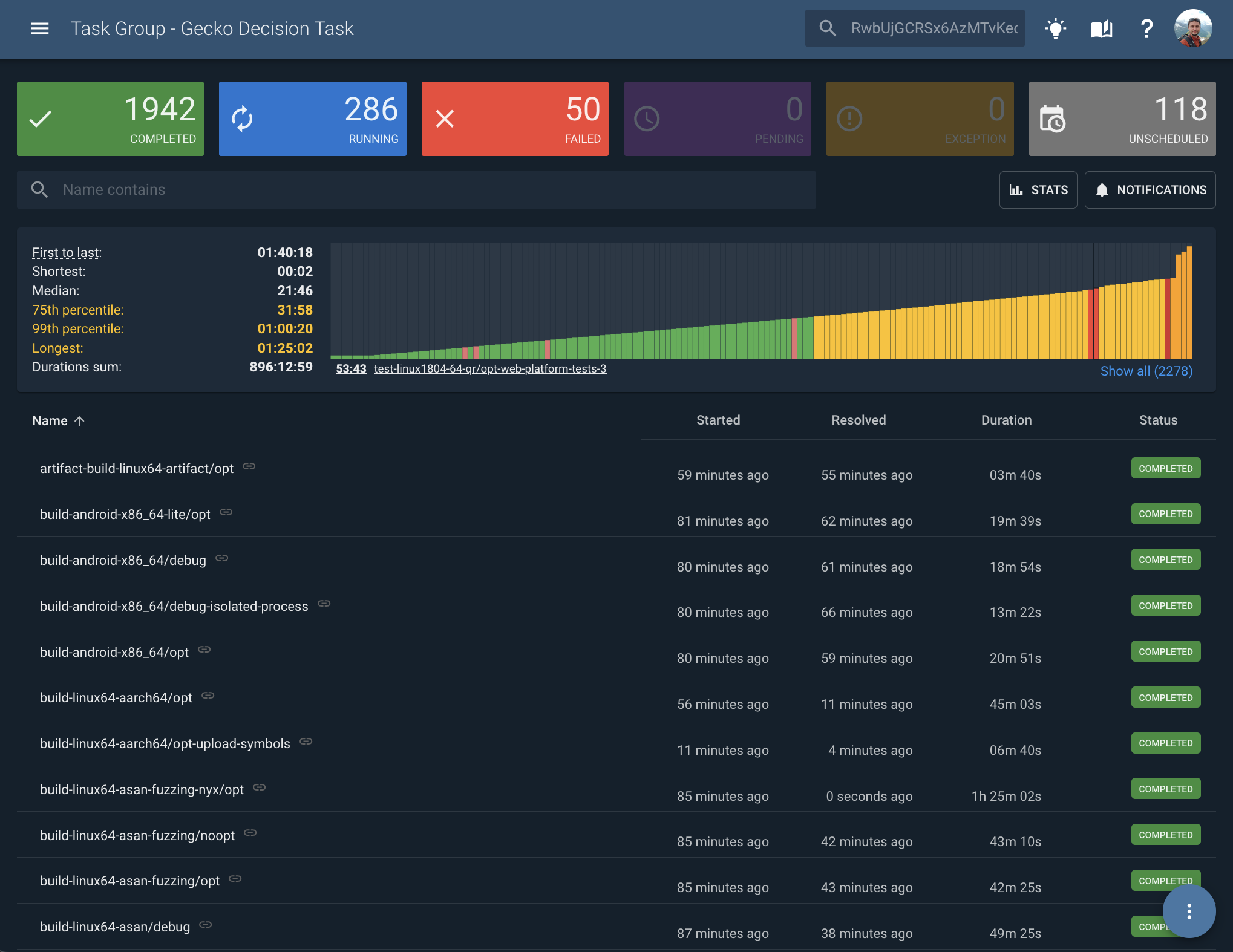

Let’s move on to the tasks. As I mentioned somewhere above, each push to mozilla-central can trigger thousands of builds. Each single push results in a Task Group being created that consists of all the tasks.

If you opened Task Group page before you would see how many tasks are in Completed state, how many Failed, how many Running. But you were not able to see which task is the longest to run? Or how long does it take to finish some task without going into each task individually.

Okay, so I want to open the Task Group page and see how long did it take for each task to complete, what was the longest one, how long it took the whole graph to resolve?

This was the first take:

I say “first” because the information presented here only gives answers to “how long it took to resolve”. Ideally it should also include information on how long do tasks need to wait before they are being executed. If tasks depend on each other it would be good to show who is waiting the longest, and few other things.

With this information you can already understand a lot. Sort by duration and see how some windows tests run for two hours. See the distribution of task times on a graph. Hover quickly to see which tasks were failing and how long it took for all tasks to complete.

It revealed that some groups might have more than a thousand compute hours to resolve. That is a lot!

Firefox Remote Settings tests

This one is rather funny and is a good example that you should always fix the root cause of the issue.

I’ve discovered that Taskcluster UI serves millions of calls a week to the unknown URLs: /api/remote-settings-dummy/v1 .. which did not belong to Taskcluster. And because default backend is ui which runs nginx that serves all requests to index.html which respond with 200 to all requests.

My first thought was to add 404 response status on nginx level to all endpoints that don’t belong there. But this will not fix the problem, calls would still be made. Luckily, Pete discovered that all those URLs are defined in the Firefox source code. Test profiles used http://localhost/api/remote-settings-dummy* endpoints. Somebody wanted to avoid doing real network calls in tests and thought that this would be enough.

However, the way that docker-worker and generic-worker work, they expose taskcluster-proxy on http://taskcluster host that enables easy way for tasks to communicate with Taskcluster (to fetch secrets, artifacts and create new tasks). However, this domain is mapped to 127.0.0.1 by default. And what happened that all http://localhost/ requests were also served by this proxy and forwarded back to the Taskcluster deployment.

That was my chance after almost a year in Mozilla to finally contribute to Firefox. Luckily, main developer of Remote Settings, Mathieu Leplatre was from my team, and he was happy to help me to submit my patch. Was a cool experiment, as the last time I used mercurial was around 2010 or so.

Here was this patch that triggered more discussions from the reviewers and I was able to patch all places and make sure things work as expected after those changes. So instead of changing two files as I initially thought, I had to change a bunch of related files and updates few tests. This was during the Christmas holidays, so it took a bit longer. Thanks to Rob Wu for being patient with the reviews.

The fix landed into 110.0a1 release.

Few days later I started to observe less and less calls to Taskcluster UI, and eventually numbers went from millions a week to just few thousands. There are still some older branches people develop against, it will take time for everyone to fetch latest changes. But to be fair, I have no idea how many developers work on Firefox source code, because you can checkout clean branch, apply few changes, and be behind 100+ commits just few hours later. Lots of things happening there.

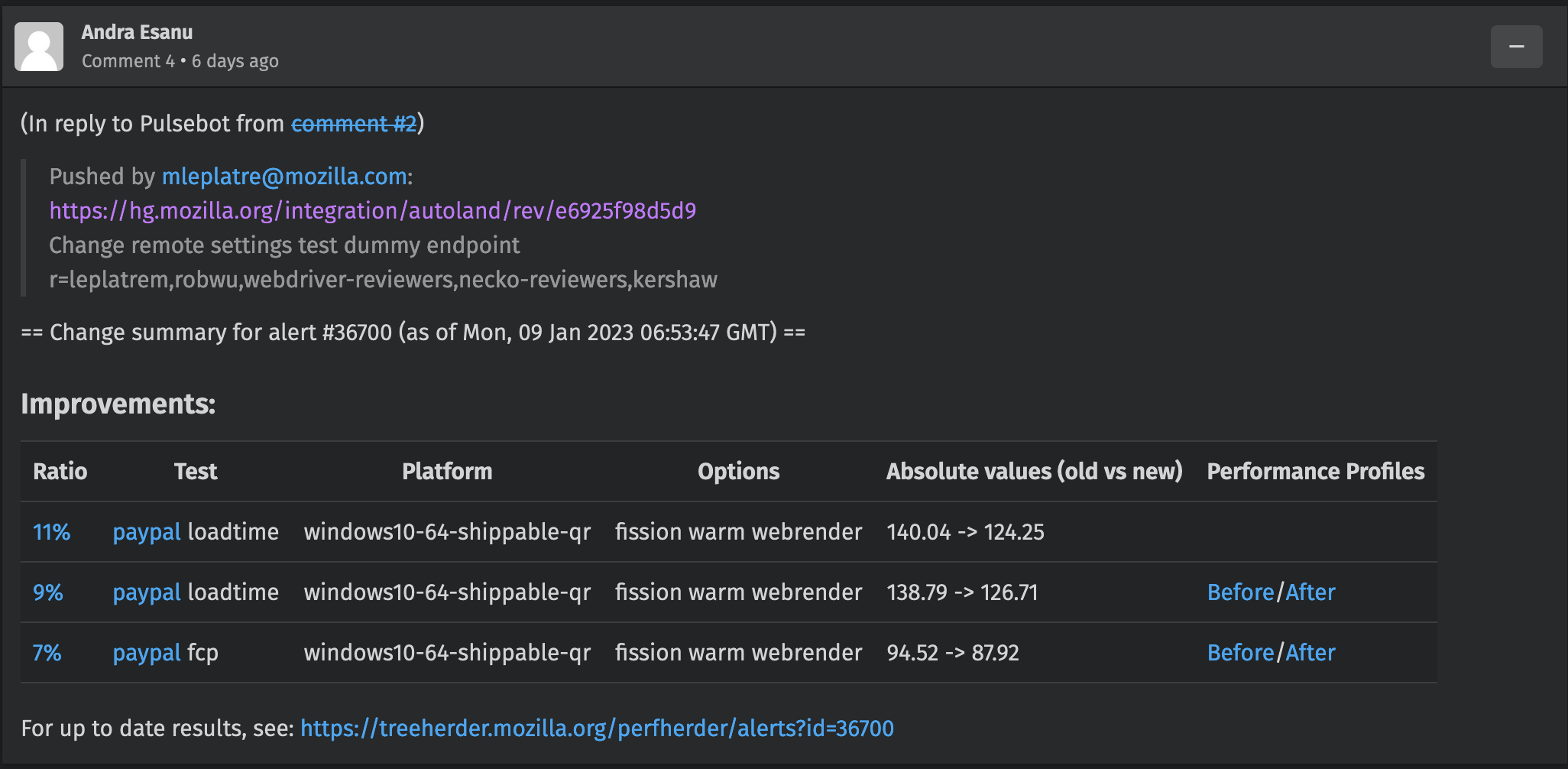

Bonus win here came few days later as someone reported 7%..11% improvement in test times. Ha! We removed network calls and now the test would finish 6s..16s faster. Awesome. Considering absolute numbers of those tests, total gain would be quite impressive. Possibly few hours to days of compute resources saved daily or weekly.

What could be done better?

Of course, mentioning just the good parts wouldn’t be fair and would mean that there were no downsides or disappointments. I’ll list some of them here.

It took me way longer to understand how Taskcluster works, and I still don’t fully understand it. It took me about two month to find to start delivering valuable patches.

I didn’t write nearly enough blog posts as I was hoping to. I had plans to write series of posts describing how Taskcluster works. So this is the first post, but hopefully not the last one on the topic.

I’ve started with E2E tests but didn’t manage to finish those. And they are not being used at the moment. Should find some time and cover more workflows and then make it run on each build.

I saw few gaps in documentation and was planning to extend it with more topics, but only managed to cover one tutorial: how to run tc locally. Improving search functionality of the documentation, along with providing client library code examples are in my future plans.

I planned to release a TUI utility to manage Taskcluster deployments. Something like k9s but for taskcluster. Being able to navigate through worker pools, workers, scopes, roles, tasks. This could be a fun tool, I just need to find more time to continue working on it.

Few times I was trying to fix something without understanding or seeing the bigger picture, which lead to increased complexity of the system. Luckily I have great team members who are willing to tell me about the alternatives.

Taskcluster’s codebase is quite old, and was created at times where ESM modules didn’t exist yet. Now, more and more libraries are switching to ESM-only packages, and it is impossible to upgrade those. This is something that we’ll need to look into and make necessary changes to the monorepo to add support to ESM modules.

I’ve also experimented with adding Typescript support to it, but didn’t have time to finish those experiments.

Another big issue is that ui uses neutrinojs that was created by great folks in Mozilla some time ago, but, unfortunately, it is no longer actively maintained. And this prevents us from doing some upgrades and changes. It is also based on older versions of webpack which are very slow in making builds and in local development. It is especially painful to build static components inside docker. The plan is here to migrate to vite and get rid of neutrino, but it wasn’t finished yet. WIP PR open since August’22.

And of course OKRs. I have a privilege on this project to decide myself what to work on, to set my own goals. Some OKRs where a hit, some were a miss. As always, it is better to under-promise and over-deliver.

And also I’ve broken few builds, which blocked few teams and made few releases roll back.

Stay tuned :)